Staff Review by Chris Saliba

Staff Review by Chris SalibaSister Carrie is Theodore Dreiser’s excoriating critique of American capitalism and society. Written over a hundred years ago, this compelling novel remains vitally relevant today.

Theodore Dreiser (1871-1945) grew up in poverty and hardship as the sixth child in a family of seven. He witnessed at first hand how tough life could be trying to survive in the American economy, without skills or education, at the turn of the twentieth century. Born in Indiana, he dropped out of school early and took on work as a reporter for The Chicago Globe. In 1894 he moved to New York City.

Sister Carrie was published by Doubleday, Page and Co. in 1900, to little fanfare. In fact, the publishers tried to rescind their contract with Dreiser after the company’s senior partners took a closer look at the manuscript, objecting to its ‘obscenity’. An absolute minimum of effort was put into publishing and promoting the book. The novel pretty much sunk without a trace, until it was reissued in 1907 after successful publication in England.

Dreiser has been noted for his naturalistic style and the realism of his work. He went one step further, using a family scandal as a central plot device. Sister Carrie is based on his sister Emma, who ran off with a married man, amongst other ill-starred adventures. Perhaps this is why the novel was titled ‘Sister’ Carrie, as nowhere else in the text is Carrie alluded to as being someone’s sister. Was this Dreiser’s secret nod to his older sibling?

The novel opens with 18-year-old Carrie Meeber travelling by train to Chicago, ready to eke out her living in that energetic yet brutal city. On the train she meets Charles Drouet, a salesman or ‘drummer’. He is a jovial type and immediately picks up that Carrie is an ingenue. He offers to taker her under his wing. Carrie, who is highly sensitive and often troubled by her conscience, gives a rather ambivalent answer to his offer of help.

Carrie can’t really take up with Drouet, because she is to move in with her sister Minnie, and her husband, Hanson. She is to board with them, as long as she can get some type of work and contribute to rent and expenses. Minnie’s house is grim and cheerless. Things are made worse by the fact that Carrie must find work, most likely of a demoralising and exploitative kind due to her lack of experience. These passages describing the back alley factories, poor working conditions and working class banter are remarkably lively. Dreiser’s skills as a reporter serve him brilliantly here, and the reader really feels taken back a hundred years to experience life as an American factory worker.

Carrie finds a job, but working for a pittance in a factory doesn’t work out, and she soon finds herself unemployed and living with her unsympathetic sister and brother-in-law. She’s seen as a liability and hopeless case. Enter Drouet, just at the right moment. He offers to set her up in an apartment until she can get on her own two feet. This relationship ambles along, until Charles Drouet’s friend, the upmarket restaurant manager George Hurstwood, takes an interest in Carrie. When George accidentally steals some money from his employer, he convinces Carrie to dump Drouet and move with him to New York. Things go from bad to worse when Hurstwood can’t find work. Pressed to desperate measures, Carrie takes work as a chorus girl and becomes, at last, financially successful, but not happy.

Sister Carrie sets a cracking pace from page one as the reader eagerly follows Carrie’s progress from poor working girl to mistress, to utter impoverishment and finally, to famous actress. Along the way, Dreiser takes the reader through every possible level of American culture and society at the turn of the twentieth century, often in almost forensic detail. We get not only realism, but the very minutiae of prices, weights, clothes, basic foodstuffs etc. In many ways the novel reads as a document of the times.

There are also moments where Dreiser shows his repugnance for American excess. Describing a dinner at an expensive restaurant, Dreiser writes:

“Once seated, there begun that exhibition of showy, wasteful, and unwholesome gastronomy as practiced by wealthy Americans, which is the wonder and astonishment of true culture and dignity the world over.”

Struggling through this tough and unforgiving world is the innocent and sensitive Carrie. Dreiser skilfully shows his heroine as someone who tries to balance what her innate morality tells her is right, against the tough imperatives of survival in a dog-eat-dog world. Hence when Carrie takes up with Hurstwood, and often displays selfish and unthankful behaviour, the reader doesn’t hold it against her. It is capitalist society which is really being judged in Sister Carrie. We understand the choices Carrie makes, because in a lot of ways, she really doesn’t have any choice. It’s either become exploited yourself, or make very shrewd decisions.

Dreiser’s moral message in Sister Carrie seems to be that American capitalism teaches people envy, useless consumption and ruthless exploitation of fellow citizens. None of it can bring happiness, which is why Carrie sits in her chair on the last page knowing that while she may be rich, she’s also miserable. This is a novel that struggles with the same themes and questions that as a society we ask ourselves today, which makes Sister Carrie particularly relevant to contemporary readers.

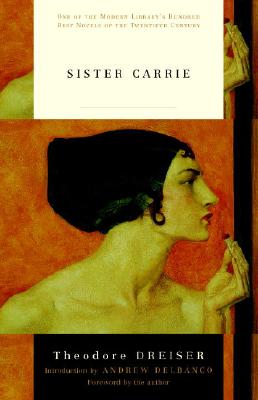

Sister Carrie, by Theodore Dreiser. Published by Modern Library Classics. ISBN: 978-0375753213 $16.95

No comments:

Post a Comment